By Md. Ashraful Haque, R&D, gtaf.org

Contributor: Md. Julhas Biswas, Marketing Executive @ gtaf.org

Today, accessing authenticated Hadith narrations on your smartphone takes mere seconds. This seamless experience—now taken for granted by millions—was nearly impossible half a century ago.

The technology behind it comes from Sheikh Muhammed Mustafa Al-Azami’s (may Allah have mercy on him) pioneering vision, extraordinary dedication, and his belief that Muslims should lead, not follow, in digitising Islamic texts.

The Spark: A Challenge That Changed Everything

Throughout Islamic history, scholars relied on physical manuscripts and printed volumes to study Hadith. Researching a specific topic meant manually searching through multiple books, depending on memory and handwritten notes. Comparing different collections required physical access to libraries, sometimes across different continents.

Earlier scholars had tried to solve this problem. Dutch researchers A.J. Wensinck and J.P. Mensing led a major project involving about 40 scholars over several decades. They published seven large reference books between 1936 and 1969. Many Hadith scholars, including Mustafa Al-Azami, used these books regularly. However, the work covered only about 25% of all Hadith literature and was only available in major university libraries.

What scholars really needed was something flexible, complete, and easy to access. But in the 1970s, computers could barely handle English text, let alone Arabic with all its special features.

Chicago, 1975: The Turning Point

During a 1975 conference in Chicago—organised by the Muslim Students’ Association to commemorate Imam Bukhari’s legacy—Dr. William Graham, a Harvard academic, proposed using computers for Hadith research. The suggestion caught the attention of Muhammad Mustafa Al-Azami, a distinguished Hadith scholar educated at Cambridge University.

Sheikh Al-Azami immediately recognised the implications. Having deeply studied Orientalist methodologies, he understood that whoever pioneered digital Hadith research would shape how these texts were perceived for generations. At that time, computer-generated findings carried significant authority—people believed computers were objective and incapable of bias.

His measured response to the proposal became prophetic: “All we ask for is a fair treatment of the subject, not a favourable one.”

This exchange sparked what Sheikh Mustafa Al-Azami’s son, Dr. Aqil M. Azami, later described as “a nightmare scenario” playing in his father’s mind. The conclusion was clear: Muslims needed to lead this technological transformation. This conviction would define the remainder of Al-Azami’s professional life.

First Step: Learning the Technology (1977-1979)

In summer 1977, Islamic organisations in Riyadh sent Sheikh Al-Azami and other scholars to the United States for educational outreach. The Muslim Students’ Association, headquartered in Indianapolis, had recently acquired a Hewlett-Packard minicomputer for their Cultural Society research centre. This became Al-Azami’s first hands-on experience with computing technology.

True to his practice of never travelling alone, Al-Azami brought his entire family.

He returned the following summer specifically to experiment with the technology. After spending a month studying the system and testing whether it could handle Arabic Hadith text, he ordered an HP2645R terminal—one of the few devices offering Arabic character support with data storage capabilities.

When the equipment arrived in Riyadh several months later, the team immediately began data entry. The technical constraints seem almost comical by modern standards: the terminal offered just 4 kilobytes of memory—your smartphone has literally millions of times more capacity. The screen displayed 25 lines of 80 characters each, with data saved one screen at a time onto mini-cartridges.

Yet the hardware limitations paled beside a far more fundamental challenge: making Arabic actually work on computers.

Technical Challenges: Breaking New Ground

Character Standardisation: Each computer manufacturer used proprietary methods for representing Arabic letters. Files created on IBM systems appeared as meaningless symbols on HP equipment. No universal standards existed.

The Diacritical Mark Problem: Arabic relies on small marks above and below letters (ḥarakāt) to indicate pronunciation—critical for meaning. The same written word can have entirely different meanings depending on these marks. For religious texts requiring absolute precision, this wasn’t negotiable. The HP terminals, however, couldn’t display these marks at all.

The team developed workarounds using substitute symbols—”/” representing one vowel sound, “” another—knowing these temporary solutions couldn’t meet scholarly standards long-term.

Developing the Marker System: Following advice from Dr. Ahmad Sharafuddeen at King Saud University’s Computer Centre, Al-Azami developed a sophisticated marking system. These non-intrusive markers identified crucial textual elements: hadith boundaries, the beginning of the Prophet’s actual words (matn), narrator names, and structural components.

Dr. Aqil M. Azami recalls his father’s dedication: “Father used to take the printed edition of Musnad Ahmad and using a red pen started filling the page with markers. The task was so demanding that father never wasted time. I remember once we were in Haram Sharief (in Makkah) waiting to pray Eid-ul-Fitr, father took out the Musnad and started writing markers all over the page.”

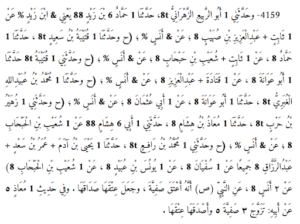

Image: A sample hadith with markers by Sheikh Al-Azami

The Breakthrough: First Mini-computer HP1000 (1979)

Encouraged by initial progress, Al-Azami made a significant decision: purchase a complete HP1000 minicomputer system with 50-megabyte hard drive, magnetic tape backup, and line printer. The price tag: $74,000—an enormous sum in 1979, paid entirely in cash.

The funding source reveals Al-Azami’s extraordinary commitment. In 1974, he had purchased a small plot in Riyadh for 28,000 Saudi Riyals through a local contact. When Saudi Arabia’s property market boomed in the late 1970s, the land’s value increased tenfold. Upon selling it for 280,000 Riyals, Al-Azami remarked: “A good deed carries tenfold rewards”—then transferred the entire amount to the United States for the computer purchase.

The system was delivered to Indianapolis in summer 1979, thoroughly tested, then shipped to Riyadh. Obtaining Interior Ministry approval for personal computer ownership required special authorisation—sophisticated computing equipment faced strict import controls.

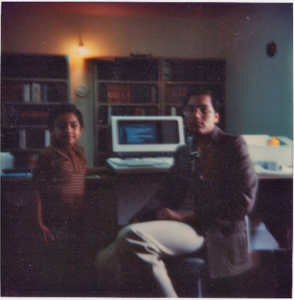

Installation occurred in the family’s third-floor university housing apartment, occupying the largest room. At that time, Aqil Al-Azami was a first-year Electrical Engineering student at Riyadh University, just learning to operate the system. Its primary use initially involved organising stored data and creating magnetic tape backups.

Image: HP1000 mini-computer in Al-Azami’s apartment – university housing

Recognition and Expansion (1980)

Al-Azami prepared an initial report of his experience on using a computer and his future plan. This report, along with two more books, was presented for consideration for the King Faisal International Prize (KFIP). In 1980, the second year of the award, Al-Azami was awarded the prize in the category of Islamic Studies (Studies involving Hadith).

The award committee acknowledged his computational project as pioneering experimental work in applying digital technology to Arabic-language Hadith research. They noted the project’s ambitious scope and the substantial effort required for completion, expressing confidence that the finished work would provide significant scholarly benefit through creation of a comprehensive electronic Hadith reference system—a resource they identified as urgently needed by researchers.

This prestigious recognition, along with the financial support it provided, enabled Al-Azami to acquire more advanced computing equipment and expand his research team.

IMAGE: Al-Azami receiving the King Faisal International Prize in 1980 and delivering speech

The Second Mini-computer HP3000 and Scholarly Expansion (1981-1983)

Taking sabbatical leave in autumn 1981, Sheikh Muhammed Mustafa Al-Azami joined the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. His son Aqil simultaneously enrolled as an undergraduate in Electrical and Computer Engineering.

As the HP1000 reached its capacity limits, Al-Azami ordered an HP3000/44 with significantly expanded capabilities: 120-megabyte hard drive, magnetic tape, and page printer. When HP introduced a 404-megabyte drive shortly thereafter, Al-Azami became an early adopter.

Sheikh Mustafa Al-Azami’s goal was now clear: create a complete digital index of Hadith words and a biographical dictionary of narrators, with computer-generated materials ready for printing. Like many Hadith scholars, he had regularly used the Wensinck-Mensing concordance and valued it—but he also saw its limits. The seven volumes indexed only a small portion of Hadith sources, leaving huge gaps. Al-Azami aimed to build a far more complete system that would fill these gaps and serve scholars worldwide.

After successfully navigating complex negotiations regarding digital typesetting equipment—including resolving technical incompatibility issues with the AM Varityper machine—Al-Azami extended his sabbatical by six months. Aqil graduated in December 1982, and the family returned to Riyadh in January 1983.

Image: Al-Azami working on HP3000

Publishing Breakthrough: Sunan Ibn Mājah (1984)

Having signed a Ministry of Education contract, Al-Azami published Sunan Ibn Mājah in 1984 as a four-volume set. Two volumes contained Ibn Mājah’s text; two volumes presented computer-generated indices including a comprehensive concordance. This represented the first Hadith book published with such extensive computer-generated reference tools.

Solving the Diacritical Mark Challenge

The HP terminal used for data entry couldn’t display Arabic diacritical marks, so all entered text lacked vocalisation. By late 1983, PC hardware with full Arabic support became available. However, by then the team had already entered Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal and all six canonical Hadith collections.

Rather than re-entering everything, Aqil spent six months developing automatic diacritisation software. Working intensively with his father on Arabic grammatical rules, they achieved approximately 80% accuracy overall, with notably higher accuracy in narrator chain (sanad) sections. This innovation saved an estimated 5-6 years of manual data entry.

Historic Achievement: The First Arabic CD-ROM (1989)

During another sabbatical in autumn 1988 at the University of Colorado (where Aqil was completing his Master’s degree), the project reached a watershed moment. Personal computers had finally become powerful enough to handle the full dataset.

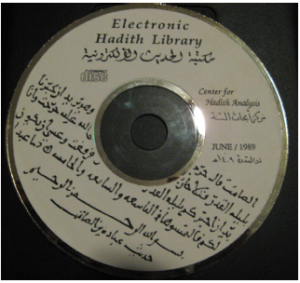

In June 1989, Al-Azami released the “Electronic Hadith Library”—a prototype CD-ROM containing the six canonical Hadith collections plus Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal, all searchable in Arabic. According to Dr. Aqil M. Azami’s account, this was the world’s first CD-ROM supporting Arabic language.

Creating this required extraordinary technical innovation. No existing platform—neither PC nor Macintosh—supported multimedia with bilingual language capability on CD-ROM. Windows 95 wouldn’t exist until 1995; earlier Windows versions (beginning with 1.0 in late 1985) supported only English. The PC environment was still dominated by the DOS command-line interface with limited bitmap fonts for Arabic.

Image: Al-Azami’s prototype hadith CD-ROM

The team built everything from scratch: custom Arabic proportional vector fonts supporting multi-level diacritical mark placement, interfaces for English and Indonesian translations of selected Hadiths, and zoomable maps showing locations and campaigns mentioned in narrations. It was genuinely multimedia decades before such technology became commonplace.

Sheikh Muhammed Mustafa Al-Azami unveiled the CD-ROM at a conference in Amman, Jordan. Subsequently, he received numerous offers from organisations working on Hadith computerisation, including from Sheikh Saleh Kamel’s Dallah Barakah group. He declined them all, explaining he wanted to work independently: “Working under some entity means his life or his child’s (the hadith project) fate is tied to the mood of the director or the board members of the funding agency, who can kill the entire project with a single stroke of a pen.”

Image: Al-Azami’s demo prototype CD-ROM

The Legacy: From One Computer to Billions of Smartphones

Sheikh Mustafa Al-Azami’s pioneering work proved that Arabic could work on computers, that automated processing could meet scholarly standards, and that technology could make Islamic knowledge accessible without losing authenticity.

By the late 1980s, commercial Hadith software began appearing. Al-Azami saw this positively, viewing his work as scholarly service, not business—created by a Hadith scholar for other scholars. His approach used verified manuscripts, whilst commercial products used printed editions.

The innovations spread quickly: digital libraries grew to contain hundreds of reference works and vast Hadith collections. Online repositories emerged. Platforms with open data access appeared, enabling new applications. Mobile apps now deliver authenticated Hadith narrations with search tools and narrator biographies directly to smartphones worldwide.

What once required travelling between distant libraries now requires simply opening an app. A village imam in Bangladesh and a university researcher in Singapore can access the same comprehensive Hadith databases.

The Principle That Endures

When commercial offers arrived after the CD-ROM demonstration, Sheikh Muhammed Mustafa Al-Azami refused them all, maintaining his independence to ensure the work served scholarship rather than commercial interests. This principle remains relevant as artificial intelligence transforms how we interact with Islamic texts.

Sheikh Al-Azami (may Allah have mercy on him) passed away on 20 December 2017 (رحمه الله). Before the new millennium, he had shifted focus toward Qur’anic studies. Shortly before his death, he expressed intentions to resume the Hadith project upon completing his Qur’anic research objectives.

Conclusion: A Vision That Continues

When you search for a Hadith on your phone and find it instantly, you’re benefiting from one scholar’s determination that Muslims should lead in bringing Islamic texts into the digital age. His courage to pursue what seemed impossible opened pathways that remain vital today.

Image: Hadith collection app by Greentech

At Greentech Apps Foundation, we build upon this legacy daily. Our Hadith Collection app represents the latest chapter in a journey that began with one minicomputer, one scholar’s sacrifice, and one transformative idea: authentic Islamic knowledge, meticulously verified, universally accessible.

—————————–

This article is part of GTAF’s R&D blog series exploring the intersection of Islamic scholarship and technology. Learn more at gtaf.org.

Reference: A.M. Azmi, 2018, “Sheikh Al-Azami’s Pioneering Work on Qur’an and Hadith-Bringing them into the Digital Era”, International Symposium on M. Mustafa el-Azami: His Life, Ideas and Contributions, Istanbul, Turkey, 19-20 December, 2018, pp. 60-77. Please check this pdf for more.

Leave a Reply